CONTENT WARNING – this article discusses assisted dying, suicide and death, which may be distressing for some readers.

As Members of Parliament (MPs) prepare to debate the Terminally Ill Adults (End of Life) Bill next week on the 29th of November 2024, the UK finds itself at a crossroads regarding compassion, ethics, and healthcare policy. The bill, proposed by Labour MP Kim Leadbeater, seeks to legalise assisted dying (AD) for terminally ill patients, reigniting a debate that has been simmering for decades.

For years, the UK has maintained laws that prevent AD, leaving many individuals with terminal conditions few options for a dignified death. If MPs approve the bill, it will move to the Committee Stage, where further details will be examined and debated. England has been prompted to follow suite after Scotland, the Isle of Man and Jersey have all made steps towards legislation this past year.

Presenter Dame Esther Rantzen, who has a diagnosis of stage 4 lung cancer, has also helped expedite this debate; she helped spearhead a petition, along with campaign Dignity in Dying, that received over 200,000 signatories that called for a change in law.

This is not the first time, however, AD has been proposed in Parliament. It was last debated in 2015, where the proposal was overwhelmingly rejected, with 330 MPs voting against and just 118 in favor. However, public attitudes have shifted significantly in recent years, and as this is a matter of individual conscience, MPs are free to vote independent of party lines. While Prime Minister Sir Kier Starmer has declined to comment at present which way he will vote and has rebuked other MPs for doing so prior to the debate; he notably voted in favour of a change in law, though, in 2015.

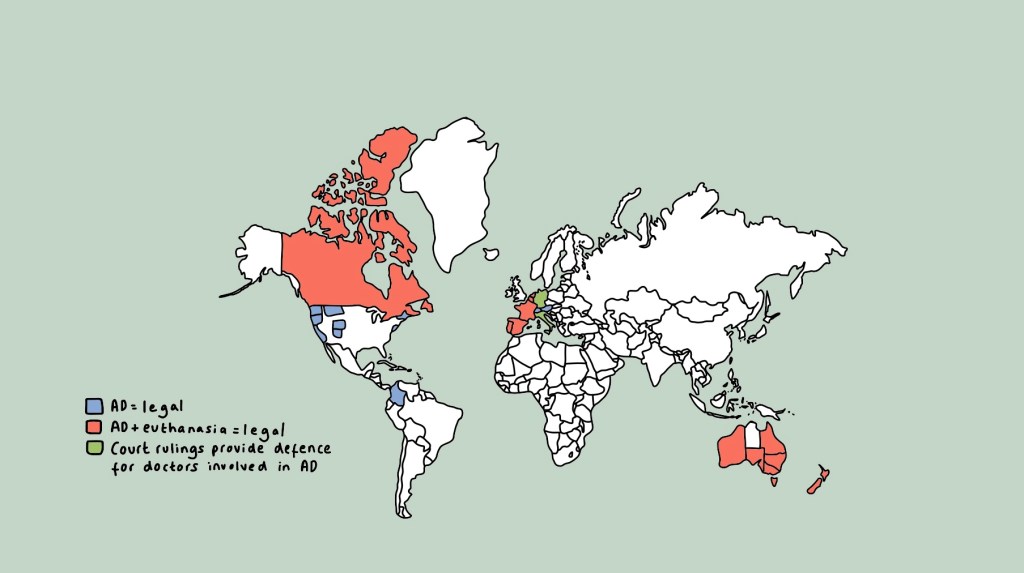

More countries have been calling their own laws on AD into question over the past few years, with countries such as the Netherlands, Switzerland and Canada, already having established legal frameworks for AD. Their experiences provide valuable insights into the implementation and regulation of such laws, including safeguards and possible eligibility criteria.

Contents

- Understanding the terminology

- Current UK laws

- A closer look at the bill

- The case for change – arguments in favour

- The case against change – arguments against

- What do physicians think?

- The way forward

- In summary

Understanding The Terminology

To properly engage with this debate, it’s essential to clarify key terms that are frequently used but often misunderstood. These include:

- Suicide – deliberately ending one’s life.

- Assisted suicide – where a physician provides the means for someone to end their life.

- Euthanasia – deliberately ending someone’s life to alleviate suffering; in euthanasia, another person administers the lethal injection, not the person who dies themself.

- Active euthanasia – direct intervention, such as a physician administering an injection, to end a life.

- Passive euthanasia – withholding or withdrawing life-sustaining treatment resulting in death.

- A form of this is already legal in the UK – Do Not Attempt Resuscitation (DNAR) forms refer to withholding or withdrawing cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR), an emergency life-saving procedure that takes place if your heart were to stop.

- Voluntary euthanasia – requested by the person who dies.

- Non-voluntary euthanasia – ending a life without the individual’s consent, typically considered murder or manslaughter.

- Assisted dying (AD) – a form of assisted suicide specifically for terminally ill patients seeking help with dying.

Current UK Laws

As of now, both euthanasia and assisted suicide are illegal in the UK. Euthanasia, depending on the circumstances, is regarded as manslaughter* or murder** by law, with the maximum penalty of life imprisonment. Assisted suicide is illegal under the 1961 Suicide Act, with those who assist in suicide facing up to 14 years in prison. However, suicide and attempted suicide are not criminal acts.

*Manslaughter = killing someone without the intention to kill.

**Murder = killing someone with the intention to kill or cause serious harm.

A Closer Look at The Bill

The bill aims to legalise AD, but only under strict criteria. For someone to be eligible, they must:

- Have a terminal illness – defined as a condition that cannot be reversed by treatment, with an expected death within the next 6 months.

- Have mental capacity* – the individual must have the capacity to make informed end-of-life decisions.

- Be at least 18 years old, be resident in England or Wales (and have been for at least 12 months), and be registered at a GP practice.

- Make a voluntary, informed, and clear request to end their life, without coercion.

Under the bill, patients must self-administer the life-ending medication, distinguishing it from euthanasia where a third party would administer the lethal dose. Doctors can prepare the medication and assist the person in ingesting it, but cannot directly administer it.

The bill also includes a robust system for safeguarding aiming to balance compassion with caution, thus protecting vulnerable individuals and ensuring that the decision is entirely voluntary and informed. These include:

- Multiple Declarations – two separate declarations must be made confirming the person’s wish, both witnessed and signed.

- Doctor’s Approval – two independent doctors must verify eligibility at least seven days apart.

- Judicial Review – a High Court judge will review and approve the application, followed by a 14-day waiting period.

- Option to Withdraw – individuals can withdraw their request at any point.

*Capacity = the ability to make an informed decision based on understanding a situation, the options available, being able to retain all information needed to make an informed decision, and the consequences of the decision.

The Case For Change: Arguments in Favour

Compassion and Relief From Suffering

A central argument in favour of AD is the desire to alleviate unnecessary suffering. Some supporters argue that when a person is enduring intractable pain and distress due to a terminal illness, it is an act of compassion to provide them with the option to die peacefully and with dignity. This is particularly significant when such suffering persists despite the best efforts of modern palliative care.

The Dignity In Dying campaign underscores this perspective, by explaining:

Dying people are not suicidal – they don’t want to die but they do not have the choice to live. When death is inevitable, suffering should not be. Along with good care, dying people deserve the choice to control the timing and manner of their death.

Terminally ill people are not choosing death over life – they are facing an inevitable death. Therefore, when death is certain and imminent, prolonged suffering in such circumstances, supporters argue, is both unnecessary and inhumane.

Furthermore, a practical example of the current gap in the law is the plight of many Britons who travel abroad to access assisted dying services, most commonly at Dignitas in Switzerland. Since 1998, 571 Britons have traveled to Switzerland to access their services, which can be emotionally and financially burdensome. For many, this option is inaccessible too, either due to cost – an estimated £10,000 – or physical incapacity due to their condition worsening. Adding to this distress is the legal risk for family members who accompany their loved ones, as assisting in suicide is punitive by up to 14 years in prison.

Legal Clarity

Another key issue highlighted by some supporters is the lack of clarity in current UK law regarding AD abroad. Right-to-die campaigners, such as Debbie Purdy, who was diagnosed with multiple sclerosis aged 31, have argued that the uncertainty surrounding whether family members could be prosecuted for assisting a loved one abroad creates additional stress for those already facing terminal illness.

Purdy won her case in 2009, which led to the publication of guidelines on when prosecution for assisting suicide would occur. However, the legal situation remains unclear, and some argue that this ambiguity forces individuals to make decisions before they are ready.

Respecting Patient Autonomy

Autonomy is one of the four pillars of ethics in medicine, and is one that recognises a person’s right to make informed decisions about their own care. Some supporters of AD argue that this should extend to decisions about one’s death, particularly when a person is terminally ill and facing inevitable suffering. If a patient fully understands their condition, prognosis, and all options, and makes a voluntary choice to end their life, they should be entitled to make that decision.

Furthermore, thresholds for an acceptable quality of life are highly subjective. What one person finds intolerable, another might accept. Respecting the right of individuals to make decisions based on their own thresholds of suffering, some advocates contend, is essential in upholding a human dignity.

Paola’s Story

For Paola, making the decision to travel to Dignitas was empowering, and a relief that her pain and suffering will be over.

Reassurance For The Terminally Ill

For some with terminal illnesses, knowing that AD is a legal option can provide immense reassurance. It allows them to regain a sense of control over their death, knowing that if their suffering becomes unbearable, they have an option to end their life on their own terms. Crucially, this does not lead to premature decisions, but rather, allows individuals to feel more in control and at peace with their condition and future.

A Reality of Uncertainty

Some argue that AD will continue to take place regardless of the law. If individuals are not able to access legal options, they may resort to illegal methods, putting themselves and their loves ones at risk. One example being in the case of Hamish Cooper in 1981; at 5-years-old he was diagnosed with terminal cancer. His mum gave him a large dose of morphine to quietly end his life, as she felt he was”facing the most horrendous suffering and intense pain”.

Legalising AD, some argue, would allow the practice to be regulated, ensuring that those who choose this path do so in a safe and supported environment.

Furthermore, supporters ask why the law should treat AD differently, when current UK law already effectively acknowledges that people have a right to die, given that suicide is legal?

The Case Against Change: Concerns and Counterarguments

Risks to Vulnerable Populations

One of the major concerns expressed by some opponents is that societal attitudes towards vulnerable groups, such as the elderly, disabled, or those with mental illnesses, may subtly shift, sending a subliminal message that assisted dying is an option they ‘ought’ to consider.

Despite safeguards being in place, critics worry that some individuals in these groups may feel coerced, either directly or indirectly, into choosing death to avoid being a burden on family, friends, health services and society.

Actress Liz Carr, supports and explores this argument in the BBC documentary Better Off Dead, a documentary she was keen to make as she feels this perspective is often overlooked. Here is a clip of her talking about this on BBC Breakfast earlier this year.

Impact on Palliative Care

A significant argument against legalising AD is the concern that it could divert attention and resources away from improving palliative and end-of-life care.

Wes Streeting, the Health Secretary, has voiced concerns that, while he previously supported AD in 2015, he now believes that the UK’s palliative care services are insufficient and need more investment before AD should be considered, as they’re currently not good enough to “give people a real choice”.

Hospice UK, while remaining neutral on the issues, has expressed concern that legalising AD could overshadow the urgent need to improve palliative care services, which already face significant funding challenges. Hospices, for example, only receive a third of their funding (£1bn) from the UK government, the rest coming from money raised by Hospices themselves. Hospice UK feel that everyone should be able to access high quality palliative and end of life care, and that funding and provision of these services should be equitable across the UK – this is currently not the case.

Dr Rachel Clarke, a UK based Doctor working in Palliative Care, has expressed similar concerns:

Assisting someone to die is far cheaper than ensuring they have the care they need to make life worth living.

Yet we don’t even fund palliative care properly as it is – let alone ‘safeguard’ dying people.

Challenges With Safeguarding

A key part of the bill is that individuals must make a voluntary, informed, and clear request to end their lives without coercion. Some opponents argue that detecting subtle forms of coercion, however, can be immensely challenging, especially in cases involving vulnerable individuals.

Palliative care physician, Baroness Ilora Finlay, explains:

“You need oversight from people who are good at identifying impaired mental capacity and good at picking up coercion. Huge numbers of people are affected by domestic abuse and it’s not detected by clinicians; they often don’t pick up coercive control.”

“Relatives may well say: ‘You’re at the point where you should take your (lethal) prescription .. or ‘Things are really bad, aren’t they?’ or ‘We don’t think we can keep you warm all winter.’ People can be coerced in all sorts of ways.”

A Slippery Slope?

Opponents of AD frequently invoke the slippery slope argument, which suggested that legislation could lead to a gradual expansion of eligibility criteria beyond terminally ill patients. Critics point to countries like Canada, where the eligibility for assisted dying has expanded over time to include individuals with chronic conditions, and mental illness.

This raises the possibility that, in the future, the law could permit AD for individuals who are not terminally ill, which could lead to unintended consequences for vulnerable people.

The Netherlands, which was the first country to legalise AD and euthanasia in 2002, exemplifies this concern. Initially focused on terminally ill patients, the law has since been extended to include individuals with dementia. The nature of this condition complicates issues of capacity and consent; before helping someone to die, it is crucial to establish whether their wishes have changed. However, when a person suffers from advanced dementia and cannot effectively communicate, how can you be certain that their preferences remain unchanged? This ethical dilemma has already resulted in legal repercussions for physicians, with one Dutch doctor facing prosecution in a related case.

Furthermore, the Netherlands allows assisted dying for minors aged over 12 and even infants up to one year old under specific circumstances. These expansions have sparked outrage among various religious groups and raised critical questions about where society should draw the line regarding eligibility for assisted dying.

Ethical and Religious Objections

Ethical and religious considerations also play a crucial role in the opposition of AD. Many Religions hold the idea of the “sanctity of life” central to their beliefs, and therefore some feel that life should not be prematurely ended regardless of suffering. For these groups, the focus should be on improving palliative care, providing spiritual and psychological support, and helping people die with dignity while allowing natural processes to take place.

Are Doctors The Right People To Be Involved In Such Decisions?

In modern clinical practice many doctors know little of patients‘ lives beyond what the busy doctor may gather in the consulting room or hospital ward. Yet the factors behind a request for assisted dying are predominantly personal or social rather than clinical.

“The problem with medicine and the institutions it has spawned for the care of the sick and the old is not that they have had an incorrect view of what makes life significant. The problem is that they have had almost no view at all. Medicine’s focus is narrow. Medical professionals concentrate on repair of health, not sustenance of the soul. Yet—and this is the painful paradox—we have decided that they should be the ones who largely define how we live in our waning days.”

Atul Gawande, Being Mortal: Medicine and What Matters in The End.

Pressures on NHS

Wes Streeting, speaking at the NHS Providers conference, warned that if Parliament legalises AD, it would signal a shift in funding priorities. He expressed concern that financing AD could come at the expense of other NHS services.

Palliative care physician, Ilora Finlay, added that legalising AD would put undue pressure on NHS clinicians, requiring up to 60 hours of clinical work per assisted death. With the recent Darzi report suggesting that the NHS is in a critical condition, some argue it lacks the capacity to support this service.

What Do Physicians Think?

Though the British Medical Association (BMA), which represents doctors and medical students across the UK, holds a neutral stance on AD. However, a survey in 2020 revealed significant divides among it’s members:

- 50% of members would support a change in law in patients being able to self-administer lethal drugs;

- Only 36% would be willing to take part in the process.

Physician’s hesitancy stems from several concerns, including increased workload, emotional strain, fear of litigation and concern for potential misallocation of resources.

If AD were to become legal, the BMA has recommended several safeguards:

- An ‘opt-in’ model for doctors to provide it.

- It should be arranged through a separate service, not through an existing pathway (i.e. a patient’s GP, oncologist or palliative care doctor shouldn’t have to arrange or deliver assisted dying as part of the standard care they provide).

- Doctor’s should have no duty to raise the issue of assisted dying with their patient, as it should not be considered a “treatment option” in the conventional sense.

- Additional funds need to be made available.

- Adequate oversight and regulation to ensure correct processes are followed.

However, not all medical groups agree with the proposed legislation. The Association of Palliative Medicine (APM), one of the world’s largest bodies of palliative care professionals, opposes the bill. Their concerns include:

- The potential harm to vulnerable groups, including those that are frail, elderly, disabled and terminally ill.

- The already inadequate funding and accessibility of specialist palliative care services across the UK.

- The erosion of trust in the doctor-patient relationship.

The Way Forward

Perhaps the most constructive approach is to view this debate not as an either/or proposition, but as an opportunity to comprehensively review and improve end-of-life care in the UK. This could include:

- Investing in palliative care services to ensure that all who need it have access to high-quality end-of-life care.

- Improving education and training for healthcare professionals in palliative and end-of-life care.

- Encouraging more open societal discussions about death and dying.

- Exploring ways to enhance patient autonomy and choice within the current legal framework.

In Summary

The debate around AD is undeniably complex, and there is no simple answer. However, it is clear that, whatever the outcome of this bill, the broader conversation about end-of-life care is crucial.

Whether or not AD is legalised in the UK, the discussions it sparks will hopefully lead to improvements in palliative care services, a greater focus on the needs of terminally ill individuals, and more comprehensive support for families.

The ultimate goal regardless of the outcome should be to ensure that every person, regardless of their condition, can die with dignity, free from suffering, and in a way that respects their autonomy.

What are your views on what constitutes a “dignified death”, and how can we best support this as a society for all individuals? What are your thoughts on the ethical implications of AD in healthcare? Do you believe that the proposed safeguards will be sufficient to protect vulnerable individuals? This is an important topic to discuss, and I’d love to hear your thoughts. Please leave a comment below!

References

Most references are hyperlinks throughout the article – see highlighted text.

https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/uk-47158287

https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/stories-47047579

https://www.bma.org.uk/advice-and-support/ethics/end-of-life/physician-assisted-dying

https://www.kingsfund.org.uk/insight-and-analysis/long-reads/nhs-if-assisted-dying-legalised

https://www.theguardian.com/society/2015/sep/11/mps-begin-debate-assisted-dying-bill

https://www.goodreads.com/work/quotes/40015533-being-mortal-medicine-and-what-matters-in-the-end

Leave a comment