Prostate cancer is the most common cancer in men in the UK, affecting 1 in 6-8 men. Every year, more than 47,000 people are diagnosed, and around 12,000 die from the disease – that’s more than 1 every hour. Despite these numbers, awareness is still surprisingly low, with many people not knowing what the prostate does, let alone the signs of cancer developing.

Prostate cancer is often called a “silent killer” because early stages may have few or no symptoms. Catching it early makes treatment simpler and more effective – stage 1 cancers, affecting only half of one side of the prostate or less, have a 5-year survival rate of almost 100%.

Today, let’s talk about everything you need to know about prostate cancer – symptoms, risk factors, prevention, testing in the UK, and more. Whether you’re a man wanting to take charge of your health, or someone looking out for your partner, father, brother, or friend, the information here could make a life-saving difference.

Contents

- What Is the Prostate, and Why Does It Matter?

- Myth-busting Health Misinformation About Prostate Cancer

- Who Is Most at Risk of Prostate Cancer In the UK?

- Symptoms of Prostate Cancer: What to Watch Out For

- What Is the PSA test, and Should I Get One?

- I’m Worried I Might Have Prostate Cancer: How Is It Diagnosed?

- Can It Be Treated? What Treatment Options Are Available?

- Prognosis

- Breaking the Stigma

- In Summary

- More Resources

DISCLAIMER:

While I am a practising doctor, the information on this site is for educational purposes only. It does not take into account your personal circumstances, which can significantly affect medical decision-making and treatment. This content therefore does not constitute medical advice, and should not be relied upon for diagnosis or treatment. Always consult a qualified healthcare provider regarding any health concerns.

This article was written on the 01/09/2025 – all information has been taken from sources that are up-to-date to the best of my knowledge on this day. Please be aware that medical information and guidelines change frequently, and this must be kept in mind when reading any health information on the internet.

What Is the Prostate, and Why Does It Matter?

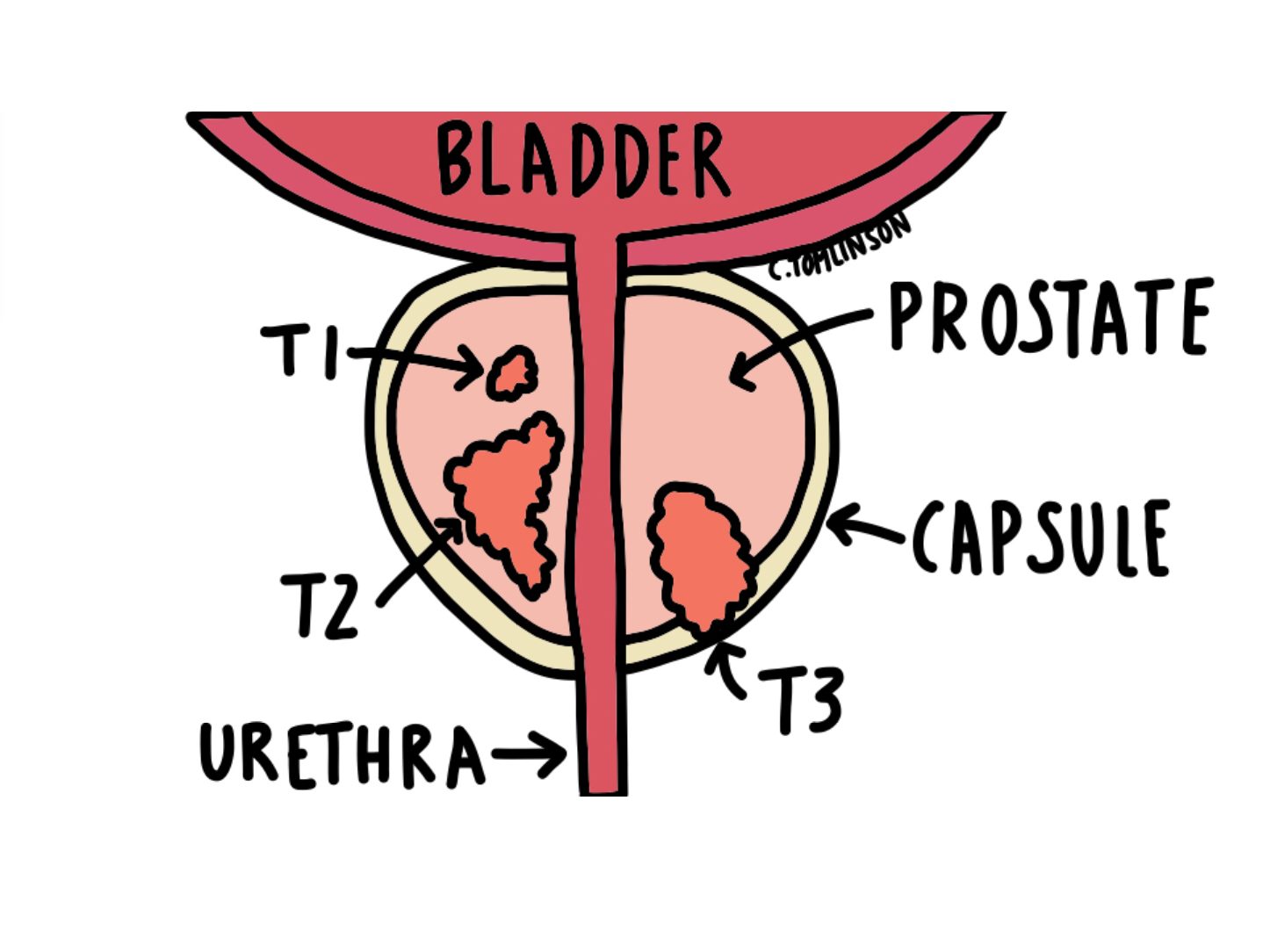

The prostate is a small gland, usually about the size of a walnut, found only in people who are assigned male at birth. It sits just below the bladder and in front of the rectum, surrounding the tube that carries urine and semen out of the body (urethra). Prostate cancer happens when cells in the prostate grow uncontrollably.

The prostate’s main job is to produce a fluid that mixes with sperm from the testicles to make semen (ejaculate). This fluid helps protect the sperm and helps it travel effectively through the female reproductive tract after sex.

Because it surrounds the urethra, any changes to the prostate – whether from enlargement, infection, or cancer – can affect urination, which is often the first sign of a problem.

Myth-Busting

There’s a lot of misinformation about prostate cancer. Let’s clear up some common myths:

- High PSA = cancer: Not always. Many things can raise PSA levels.

- Trans women can’t get prostate cancer: They can, because typically the prostate is kept in gender-affirming surgery.

- Only old men get prostate cancer: Risk rises after 50, younger men can still be affected, especially if they’re Black or with a family history of it.

- All prostate cancers need immediate treatment: when the “C” word is mentioned, we are very keen to act quickly. Many prostate cancers, however, are slow-growing, giving time to consider options and make a decision that is right for you with help from your specialist team.

- Difficulty urinating = cancer: Other conditions like an enlarged prostate or prostatitis can present similarly, but always get it checked.

Who Is Most at Risk of Prostate Cancer in the UK?

Risk factors include:

- Age over 50 years – By 80, 70% of men show evidence of prostate cancer.

- Black ethnicity – 1 in 4 black men will be diagnosed with prostate cancer, as opposed to 1 in 8 white men; their risk is doubled.

- Prostate cancer in a close relative (brother, father, or son).

- Inherited genes – faulty BRCA2 gene (which also increases the risk of breast and ovarian cancer, too), and possibly BRCA1 too (though evidence is mixed), Lynch syndrome (caused by faulty MLH1+2 genes).

Symptoms of Prostate Cancer: What to Watch Out For

As prostate cancer typically starts in the outer part of the prostate, there are often no early symptoms until the cancer has grown. As it grows, it starts to press on the urethra, which is why a change in your waterworks is often one of the first signs.

Possible warning signs include:

- Difficulty starting or stopping urination, having to strain to have a wee, and feeling as if your bladder isn’t emptying fully.

- Weak flow, urine flow that starts and stops, or needing to urinate often, especially at night.

- Blood in urine or semen.

- Erectile dysfunction – being unable to get or maintain an erection.

- Pain in the lower back, hips, or pelvis.

- Tiredness, unintentional weight loss.

These symptoms don’t always mean it’s cancer – they can also be caused by an enlarged prostate, prostatitis (inflammation of the prostate), or other conditions. Still, it’s important to get them checked by your GP.

What Is the PSA Test, and Should I Get One?

The NHS does not offer routine prostate cancer screening, but men over 50 (or 45 for higher-risk groups) can request a PSA test. This is a simple blood test that checks levels of prostate-specific antigen, a protein that is produced by the prostate.

The PSA test may pick up on prostate cancer before symptoms develop, and it increases the likelihood that it is detected early, where there may be more treatments available and prognosis may be better.

A high PSA on the blood test doesn’t always mean it is cancer, though.

That’s the tricky part. The PSA test isn’t perfect, and that’s why UK NICE* guidelines do not currently recommend it as a routine screening tool for all men. Here’s why:

- False positives: Many men with raised PSA levels don’t have cancer (around 75%). Conditions like an enlarged prostate, infection, or even recent exercise/ejaculation can cause a high PSA. This can lead to unnecessary anxiety and further invasive tests that aren’t needed.

- False negatives: Some men with prostate cancer have a normal PSA level (around 15%), so the test can miss cancers that are present.

- Overdiagnosis: The test can pick up very slow-growing cancers that might never have caused harm. Treating these can sometimes do more damage than leaving them alone, because surgery and radiotherapy carry their own risks, like incontinence and erectile dysfunction.

Instead of using it in a screening program, the PSA test is offered through the “Prostate Cancer Risk Management Programme.” This means:

- Men over 50 can request a PSA test after talking through the pros and cons with their GP.

- Men at higher risk (such as Black men or those with a family history) are encouraged to have that discussion earlier, from around age 45.

*NICE = National Institute for Health and Care Excellence, an organisation that makes evidence-based recommendations for health and care in the UK.

I’m Worried I Might Have Prostate Cancer: How Is It Diagnosed?

If you visit your GP with symptoms or concerns about prostate cancer, they’ll usually start with a discussion of your risk factors (such as age, family history, and ethnicity) and a review of your symptoms. From there, some initial tests may be carried out:

- Digital Rectal Examination (DRE) – an examination of your back passage. To do this, the doctor gently inserts a gloved finger into the rectum to feel the prostate. They’re checking for size, shape, or any hard or lumpy areas.

- It can feel awkward or daunting, but it’s quick and shouldn’t be painful, and often provides important clues.

- If you have any discomfort for any reason during the examination, you can ask your healthcare practitioner to stop.

- You can also ask to see a Doctor of the same sex if that would help you feel more comfortable.

- PSA blood test – high levels may suggest a problem, but as discussed earlier, it doesn’t always mean cancer.

If your PSA test is raised, or your Doctor is concerned, they will refer you on the urgent suspected cancer pathway (previously known as the “two-week wait” pathway). Being referred on this pathway doesn’t necessarily mean you have cancer; it is a pathway that means you’ll be seen more quickly, to help pick up on possible cancers early. 9 out of 10 people referred on this pathway will not have cancer.

In secondary care (hospitals), some further testing may be done:

- Multiparametric MRI scan of the prostate is usually done first. This scan gives a detailed picture and helps doctors decide whether a biopsy is needed. In many cases, the MRI can rule out cancer without needing further invasive tests.

- Prostate biopsy – if the MRI shows a suspicious area, then small samples of the prostate will be taken to look for cancer cells. The samples are then looked at under a microscope.

If cancer cells are found, Doctors will assess how aggressive it is using the Gleason score – the higher the Gleason score, the more aggressive the cancer is (and the more likely it is to spread). The cancer will then also be staged – this looks at how big an area is affected, and to what extent its spread throughout the body.

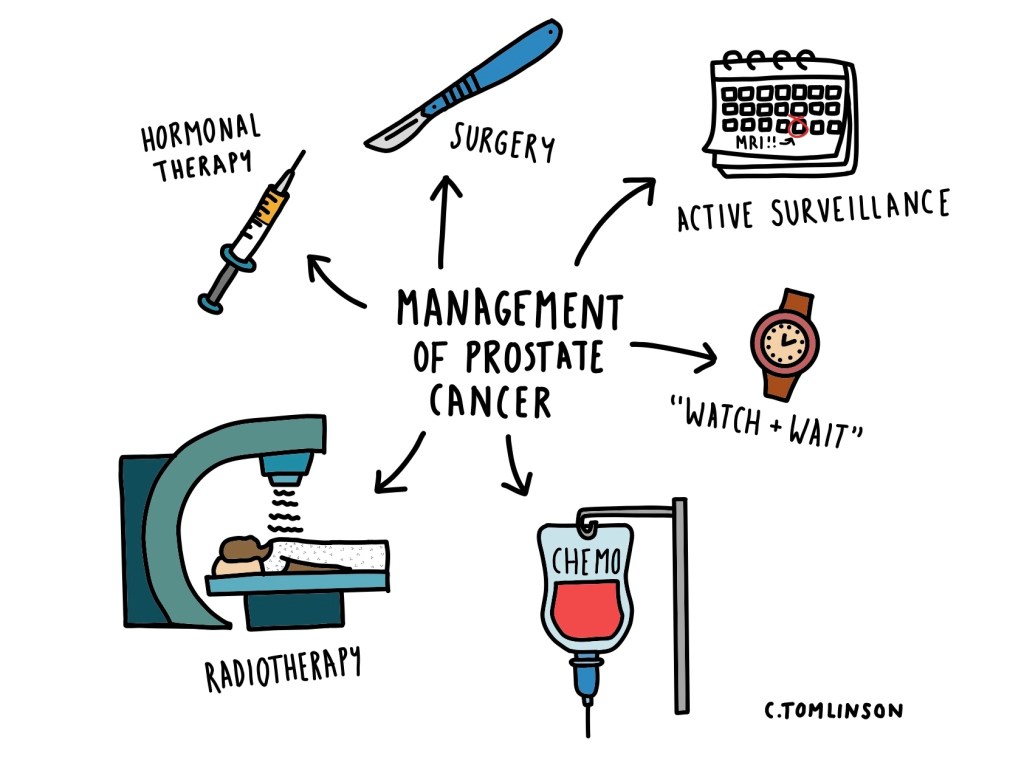

Can It Be Treated?

Treatment for prostate cancer isn’t the same for everyone — it depends on the stage of the cancer, how aggressive it is, and your overall health. Some prostate cancers grow very slowly and may never cause harm, while others need treatment straight away.

Active Surveillance

This option tends to be for slow-growing cancers that are unlikely to cause symptoms or to shorten life-expectancy. It involves regular reviews, PSA tests, MRI scans, and sometimes repeat biopsies.

Treatment will considered if the cancer begins to grow or change, and generally any treatment started will be with the aim of curing the cancer, though this varies depending on factors like your general health, your age, and the stage of the cancer.

“Watchful Waiting”

This tends to be for slow-growing cancers, if you have other health problems so you can’t have treatment to try and cure the cancer, if you don’t want to have treatment to cure the cancer, or if you’re diagnosed at an older age so any treatment is unlikely to affect your life-expectancy.

You’ll have a PSA test at least once a year, and monitoring is usually done by the GP.

If you develop any symptoms or if your PSA suddenly rises, then you will be reviewed by a prostate cancer specialist. They may recommend starting hormonal treatment, typically with the aim of shrinking it/slowing growth, not curing the cancer.

Surgery For Prostate Cancer

This is known as a “radical prostatectomy“, where the prostate gland is removed, along with the cancer cells within it. This can be done under keyhole surgery* which can be done by hand or using a robot**, or open surgery***.

This tends to be an option for cancers which haven’t spread outside of the prostate (localised prostate cancer) or if it has only spread to the area just outside the prostate (locally advanced prostate cancer). It may also be an option if the cancer comes back after radiotherapy (recurrent prostate cancer).

There are some possible side effects from surgery, such as problems with incontinence, or difficulty getting or maintaining an erection, for example.

*Keyhole surgery (also known as a laparoscopy) = an operation that is minimally invasive to the body, where a few small cuts are made into the abdomen, and special tools are used (one being a camera) to operate inside the abdomen without having to open it up.

**This is known as the ‘da Vinci® Robot‘. The surgeon remains in the theatre during the operation but controls the machine from the console. In my second year as a doctor, I had the opportunity to see the robot in use during robotic colorectal operations – an experience I found fascinating!

***Open surgery = a larger cut is made instead of multiple small ones.

Hormonal Treatments

The hormone testosterone can make prostate cancer cells grow. Hormone therapy aims to lower testosterone levels or blocks its effect, slowing the cancer’s growth. It is usually given by injection (e.g., Zoladex or Prostap) or in tablet form (e.g., Casodex). Hormonal therapy can be used at all stages, even if the cancer has spread, and is often used alongside other treatments such as radiotherapy.

Hormone therapies do not cure prostate cancer, but help slows its growth and can help with symptoms. Treatment with these drugs is also known as “medical castration“, because they are very effective at lowering testosterone levels.

Sometimes an orchidectomy (removal of the testicles) can be used as a hormonal therapy. This works as the testicles produce testosterone, so removing them can help lower testosterone levels. It is rarer to have this now, with hormonal injections or tablets being much more commonplace as they are less invasive.

Radiotherapy

This is where high-energy radiation is used to kill cancer cells, or slow their growth. It can be used to try cure the cancer (curative radiotherapy), before or after surgery, alongside other treatments like chemotherapy to help make them more effective, or to help improve symptoms if curing the cancer isn’t possible (palliative radiotherapy).

There are several types that are used in prostate cancer treatment:

- External beam radiotherapy: high-energy radiation is directed at the prostate from outside the body.

- Brachytherapy: tiny radioactive “seeds” are placed inside the prostate, where they slowly release radiation over time. This directly targets the cancer, whilst limiting damage to surrounding tissues by radiation.

- Radioisotope therapy: used mainly when the cancer has spread to the bones, a small amount of radioactive substance (such as Radium-223) is injected into the bloodstream, where it travels to cancer in the bones and delivers radiation directly to those cells.

As sometimes healthy cells can also be damaged by radiotherapy, there can be a few side effects such as tiredness, loss of appetite, or an upset stomach.

Chemotherapy

Chemotherapy drugs (like docetaxel) attack fast-growing cancer cells, which can help to shrink them and slow down their growth. This is used if the cancer has spread beyond the prostate (advanced prostate cancer), or if the cancer isn’t responding to hormonal therapy (castration-resistant prostate cancer).

There can be quite a lot of side effects with chemotherapy which can be difficult to deal with, for example: tiredness, hair loss, lowered immunity and increased infection risk (due to reduced white blood cells), nausea and vomiting, bowel upset, and numbness in hands/feet. There are ways your healthcare practitioner can help with these symptoms, though.

Newer (And Future) Treatment Options

- Radionuclide Therapy (PSMA Therapy): Uses radioactive substances such as Lutetium-177 PSMA that attach directly to “Prostate-Specific Membrane Antigen” (PSMA), a protein found on the surface of prostate cells, delivering targeted radiation. This is mostly used in cases where the cancer has spread (“metastasised”) around the body, and has shown promising results in clinical trials.

- PARP Inhibitors (e.g. Olaparib): Work for men with certain genetic changes (like BRCA1 or BRCA2 mutations). These drugs stop cancer cells from repairing themselves, making them more likely to die off. It is used in castration-resistant prostate cancer.

- Immunotherapy: Some treatments, e.g., pembrolizumab, are designed to help the immune system recognise and attack prostate cancer cells. These are currently being used in clinical trials in the UK.

Prognosis

Prognosis (long-term outlook) for prostate cancer is usually very good, especially if it caught early.

According to Cancer Research UK, 5-year survival rate by stage is:

- Stage 1 (T1, too small to be picked up on scans or felt on DRE, but can be picked up on biopsy) – almost 100%.

- Stage 2 (T2, contained within the prostate) – almost 100%.

- Stage 3 (T3, the cancer has broken through the covering around the prostate, known as the “capsule” – around 95%.

- Stage 4 (T4, the cancer has spread to nearby organs e.g. bowel, to lymph nodes, or to other parts of the body e.g., bones or lungs) – around 50%.

As prognosis is influenced by lots of different factors, it can be difficult to tell exactly what it will be. You will need to speak to your specialist about your individual prognosis.

Breaking the Stigma

Even though prostate cancer is the most common cancer in UK men, many avoid talking about it. There are different reasons for this:

- Embarrassment about urinary or sexual symptoms – this can feel awkward to talk about, whether its with friends, loved ones, or even with your Doctor (rest assured though, we’re very used to talking about these things!).

- Symptoms are dismissed, and often put down to “ageing” – while age-associated changes (such as pelvic floor muscle weakness) may play into your symptoms, it is worth having a chat with your Doctor if you develop anything that is new or unusual for you, especially if you are aged over 50.

- Fear of the DRE – though it can seem daunting, it’s quick, painless, and can be vital for early detection.

- Reluctance to talk about men’s health – there’s a cultural expectation that men should “tough it out” and not complain about health problems. This stoicism means many don’t seek help until symptoms are more severe.

- Concerns about treatment and side effects – treatments for prostate cancer can affect sexual function, fertility, and continence, but as can prostate cancer if left untreated! Men may fear losing part of their identity, masculinity, or quality of life, which can make them avoid testing or treatment.

- Lack of awareness in younger men – because prostate cancer is most common in men over 50, it is often not at the forefront of younger men’s minds. However, you can still get it when younger, especially if you’re at higher risk.

In Summary

Prostate cancer is the most common cancer in UK men, affecting around 1 in 6–8 men. Despite its prevalence, many people are unaware of what the prostate does, the warning signs of cancer, or the risk factors that increase the likelihood of developing the disease. Early detection is key – when caught early, prostate cancer is highly treatable, and many men go on to live long, healthy lives. Knowing your risk, paying attention to changes in urination or sexual function, and speaking openly with a mate, dad, partner, or your GP can make all the difference.

Resources

Movember – a charity aiming to change the face of men’s health, with a specific focus on prostate cancer, testicular cancer, and mental health. Read more here:

Cancer Research UK has a really extensive list of resources you may find useful if you, or someone you know, has recently been diagnosed with prostate cancer:

Advice for men on PSA testing when they don’t have any symptoms of disease:

More information on all things prostate cancer from Prostate Cancer UK:

https://prostatecanceruk.org/prostate-information-and-support

Leave a comment